Colaboration by Gerardo Leal

Classes in JavaScript

In ES2015, the keyword class was introduced to provide a cleaner syntax to create objects in JavaScript, and more familiar to other Object Oriented Programming (OOP) languages like Java or C++.

In JavaScript, a class definition looks like this:

class Car {

constructor(brand) {

this.brand = brand

}

start() {

console.log("starting car of brand", this.brand)

}

}

const bmw = new Car("BMW")

const bugatti = new Car("Bugatti")Before ES2015, a different syntax was required to achieve the same thing:

function Car(brand) {

this.brand = brand

}

Car.prototype.start = function () {

console.log("starting car of brand", this.brand)

}

const bmw = new Car("BMW")

const bugatti = new Car("Bugatti")But, in practice, they both work exactly the same. Class it's actually a special kind of function that is declared with a different syntax.

Prototype

Prototype-based programming is a style of object-oriented programming in which behavior reuse (inheritance) is possible by using existing objects that serve as "prototypes". So a "class" (in its strict form) is really never defined, but rather an object is created and reused as the implementation for other objects.

This is all possible via a special link between objects called [[Prototype]].

The prototype object

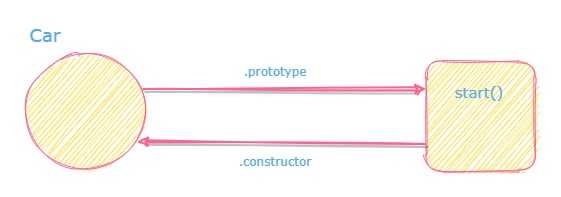

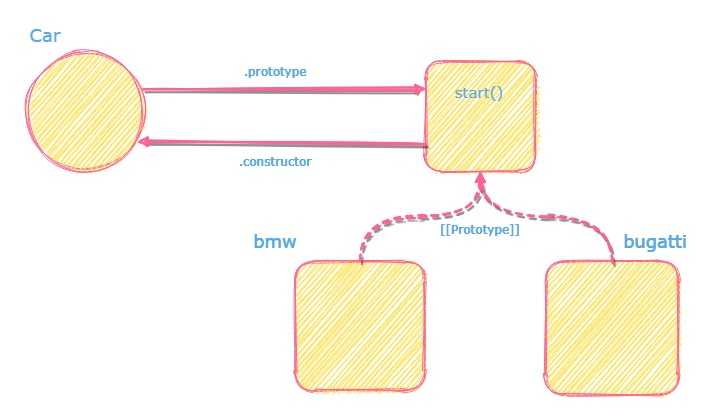

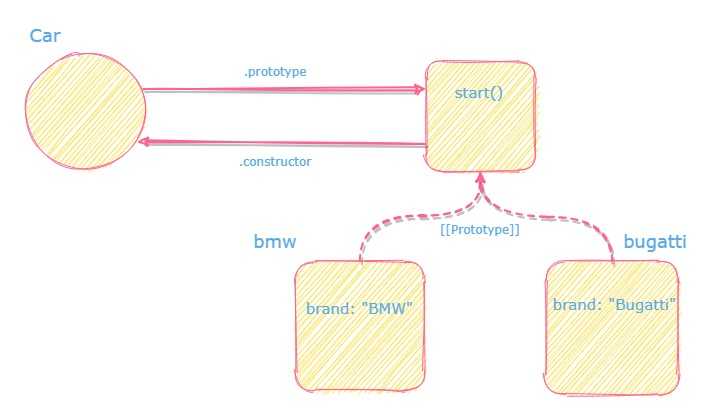

When a function (or a class) is defined, an object called "prototype object" is created in memory and linked to it via the ".prototype" property. A reciprocal link from that object to the function is also created called ".constructor" property.

As seen in the function example, you can interact directly with that object using the ".prototype" property, for example, to declare methods like the start() method of our Car.

With the class syntax, this implementation detail is hidden from us, but the same thing is happening under the hood.

The [[Prototype]] chain

class Car {...}

const bmw = new Car("BMW");

const bugatti = new Car("Bugatti");When a new object is created using new Car(...) , a series of operations take place:

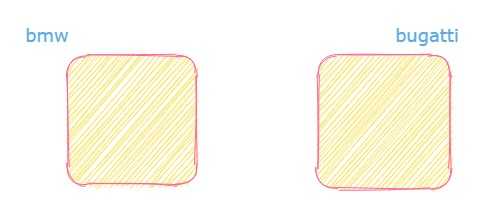

1. A brand new object is created in memory.

This object is completely empty (no methods, no properties).

2. The [[Prototype]] link is created.

So at this point the object is already linked to the "prototype object" of function (or class) Car.

3. The function is executed (constructor call) using the newly created object as the value of this

It's at this point where the brand property is defined and assigned. It's important to notice that the brand property is defined inside EACH object, and is not part of Car "prototype object".

In case of the class syntax, the constructor method is the one executed at this stage.

Think of it as JavaScript calling the Car function as follows:

function Car(brand) {

this.brand = brand

}

const bmw = Car.apply({}, "BMW") // {} is the newly created object in memory

// it's not really what's happening but it serves to ilustrate

// how the new object gets its properties defined.4. A reference to this newly created object is returned:

And generally, that reference is stored in a variable (bmw and bugatti in this example) in order to access the object later when needed.

class Car {...}

const bmw = new Car("BMW"); // stored reference to object with "BMW" brand

const bugatti = new Car("Bugatti"); // stored reference to object with "Bugatti" brandWalking the [[Prototype]] chain

When executing the method start for each object, two things happen:

class Car {...}

const bmw = new Car("BMW");

const bugatti = new Car("Bugatti");

bmw.start() // starting car of brand BMW

bugatti.start() // starting car of brand Bugatti1. Finding the method in the [[Prototype]] chain

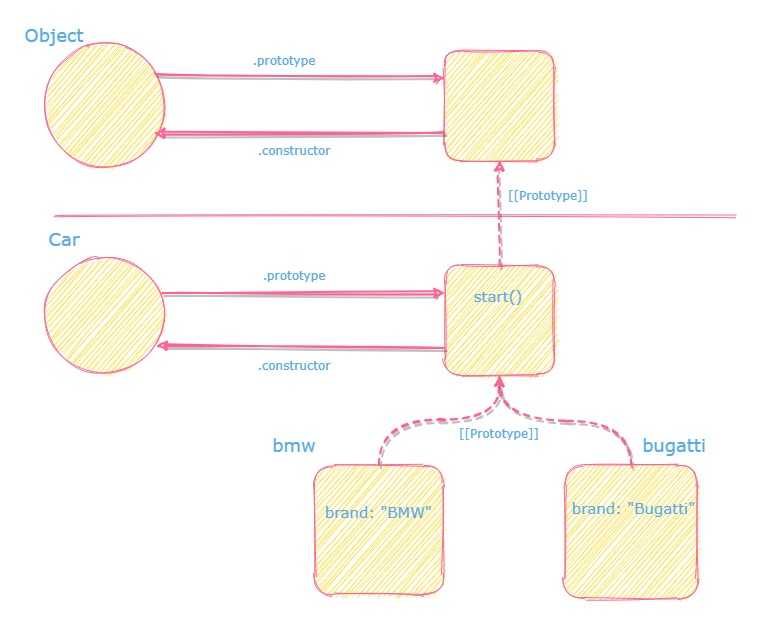

If we take a look at the diagram of the newly created object, you'll notice they don't have a start method, only a brand property. So how is it that we can execute the method?

JavaScript has a special behavior for objects when it tries to GET the method from them. If it cannot find it, it will follow the [[Prototype]] chain to the next linked object and look for it there. It will continue doing this until if finds the method and execute it, or throw an error.

This is what makes it possible for bmw and bugatti to use the start() method of the prototype object of Car.

2. Using the object as the value of this

The second part of the magic is actually something we've seen before. How is the correct brand printed to the console?

As we already explored in the this blog, the implicit binding rule states that when a function is executed as a method of an object, such object is used as the value of this.

So no matter where in the [[Prototype]] chain the function is found, since it was called as a method of either object bmw or bugatti, the value of this is correctly set.

No magic! Just JavaScript following the rules we already know.

The end of the [[Prototype]] chain

So now we've seen how JavaScript finds a method or property in the [[Prototype]] chain, but where does it end?

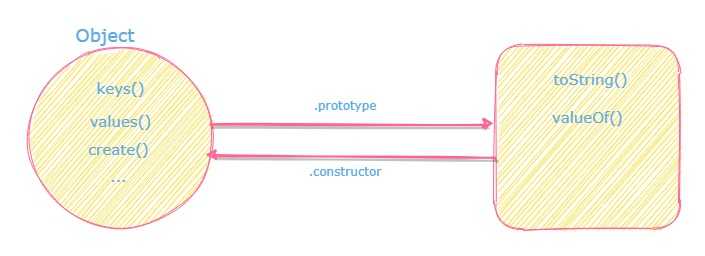

There's a single class, let's say it's the "original" class, called Object (with capital O) and has it's own "prototype object". All other objects in JavaScript are linked, either directly or indirectly, to this original Object through the [[Prototype]] chain.

This Object has a collection of methods and properties that may seem familiar:

So the look up in the [[Prototype]] chain ends when it reaches Object:

All other primitive objects like Function, String or Number are linked to this original Object as well.

Prototypal Inheritance

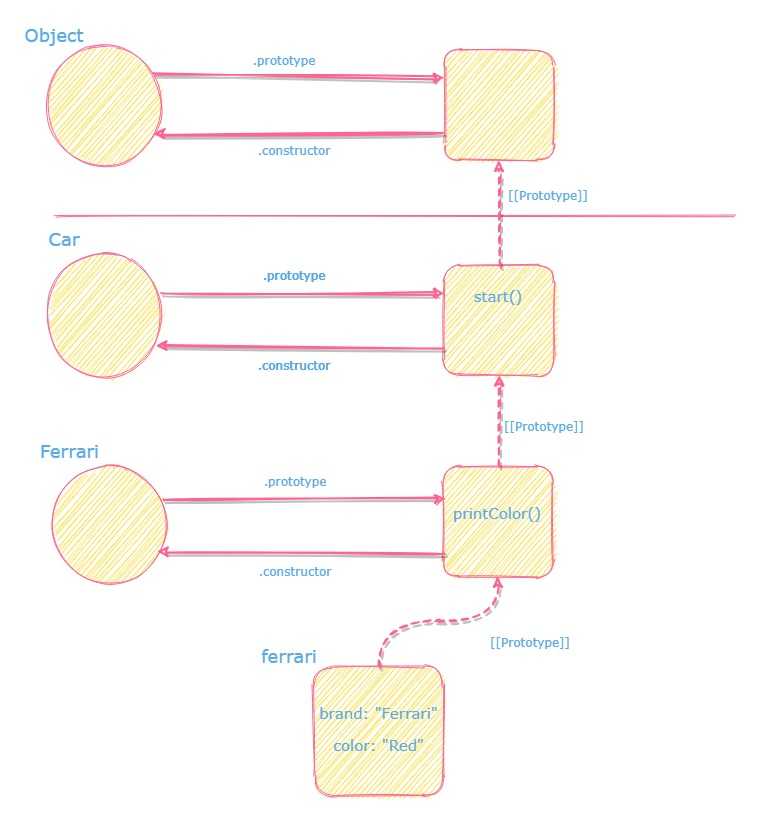

It is possible in JavaScript to "extend" a class, creating another one that will have the behavior of the extended one, plus new features. Let's take for example that we want to create a class Ferrari that's still a car with a brand and a start(), but has more features like a limited amount of colors.

With ES2015, the syntax would look like this using the extend keyword:

class Car {

constructor(brand) {

this.brand = brand

}

start() {

console.log("starting car of brand", this.brand)

}

}

class Ferrari extends Car {

constructor(color) {

// calling the constructor method of class Car. All Ferrari are of brand "Ferrari"

super("Ferrari")

// throw an error if setting an invalid color

if (color !== "Yellow" && color !== "Red") {

throw new Error("Ferrari should only be of color yellow or red...")

}

this.color = color // otherwise, set the color.

}

printColor() {

console.log("This Ferrari is of color", this.color)

}

}

const ferrari = new Ferrari("Red")

ferrari.start() // starting car of brand Ferrari

console.printColor() // This Ferrari is of color RedYou may be tempted to think that by "extending" class Car , you're creating a copy of all its methods and properties and adding them to Ferrari. But no, we're actually just linking objects together! This time, "prototype objects" together:

Notice the super() call in Ferrari constructor. That's a special keyword that comes along with the class syntax to call the constructor of the extended class Car. That call is the one that initializes the brand property of our ferrari.

When executing the methods, the same principle of the [[Prototype]] chain is applied: if a method doesn't exists on an object it will look it up in the next linked object until it finds it of fails. That's why our ferrari has also the method start().

The same can be achieved with plain functions and prototype manipulation directly, but you'll probably notice it involves a little more code and knowing what to link:

function Car(brand) {

this.brand = brand

}

Car.prototype.start = function () {

console.log("starting car of brand", this.brand)

}

function Ferrari(color) {

Car.call(this, "Ferrari") // Constructor call to also initialize whatever Car does.

// throw an error if setting an invalid color

if (color !== "Yellow" && color !== "Red") {

throw new Error("Ferrari should only be of color yellow or red...")

}

this.color = color // otherwise, set the color.

}

// Object.create creates an empty object, and link it to a given object

// Kind of like step 1 and 2 of calling `new`.

Ferrari.prototype = Object.create(Car.prototype)

Ferrari.prototype.printColor = function () {

console.log("This Ferrari is of color", this.color)

}

const ferrari = new Ferrari("Red")

ferrari.start() // starting car of brand Ferrari

console.printColor() // This Ferrari is of color RedClassical OOP vs Prototypal

JavaScript OOP it's just objects linked to other objects...

Classes aren't really classes

In classical OOP, classes serve as a "blueprint" of what an object should look like, they are just abstractions. The only thing you can do with them is "create object" of extend them.

As you've seen, even if JavaScript now includes a class keyword (with super and extends), they are just functions with objects linked to them, and it's the objects the ones that hold an implementation of methods and properties.

Objects don't get a copy of the methods when instantiated

In classical OOP, every object created also receives a copy of the methods and properties that the class defines.

With prototypal OOP, objects don't get a copy but rather a link to another object that already has the implementation, and relies on "behavior delegation" to achieve the inheritance effect.

You can add methods and properties to prototypes in runtime

In classical OOP, you can't add more properties or methods to a class in runtime. It all happens when you write and compile your code.

In prototypal OOP, you can add more methods and properties to a class in runtime, and all the objects linked to that will also have access to this new properties/methods:

class Car {

constructor(brand) {

this.brand = brand

}

}

const bmw = new Car("BMW")

function addStop() {

Car.prototype.stop = function () {

console.log("stoping car of brand", this.brand)

}

}

// ... anywhere else

addStop()

// and now bmw has that new method

bmw.stop() // stoping car of brand BMW.OOP techniques with prototype

Shadowing methods

There are cases where one of the objects need a specific behavior for a inheritance method. For this, there's a way to add a method of the same name and even reuse some of the logic of the original method if needed

class Car {

constructor(brand) {

this.brand = brand

}

start() {

console.log("starting car of brand", this.brand)

}

}

const ferrari = new Car("Ferrari")

// method shadowing

ferrari.start = function () {

this.start()

console.log("FERRARI BABY!!!")

}

ferrari.start()

// starting car of brand Ferrari

// FERRARI BABY!!!A more practical scenario is when extending classes, and the new class needs a different behavior for the same method:

class Car {

constructor(brand) {

this.brand = brand

}

start() {

console.log("starting car of brand", this.brand)

}

}

class Ferrari {

constructor() {

super("Ferrari")

this.started = false

}

start() {

super.start() // calling Car.start

this.started = true

}

}

const ferrari = new Ferrari()

ferrari.start() // starting car of brand ferrari

ferrari.started // trueStatic methods

In OOP there's a notion of static methods. Static methods aren't called on instances of the class. Instead, they're called on the class itself. These are often utility functions, such as functions to create or clone objects.

For ES2015 class syntax, a special static keyword is provided:

class Car {

constructor(brand) {

this.brand = brand

}

start() {

console.log("starting car of brand", this.brand)

}

static isColorVailable(color) {

const availableColors = ["red", "blue"]

return availableColors.includes(color)

}

}

const ferrari = new Car("Ferrari")

ferrari.isColorVailable("blue") // TypeError: ferrari.isColorVailable is not a function

Car.isColorVailable("blue") // trueReference

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Classes

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Glossary/Prototype-based_programming

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Object/proto

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Classes/static

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prototype-based_programming

- https://frontendmasters.com/courses/deep-javascript-v3/prototypes/

- You Don't Know JS: This and Object Prototype: Book by Kyle Simpson